As Plumvillage.Org completes their livestream schedule of events memorializing the life of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh, I share a recent article by Norm Stockwell, the publisher of the Progressive Magazine. Norm and I were co-conspirators on a number of projects in the past, and I feel honored that my old friend reached out to me as he wrote the article.

With a deep bow of appreciation to Thay, to Norm, and to all those who devote their lives to the welfare of this planet and its many beings, here is the article:

The Passing of Thich Nhat Hanh

Late monk used engaged Buddhism to build a foundation for a peaceful world.

|

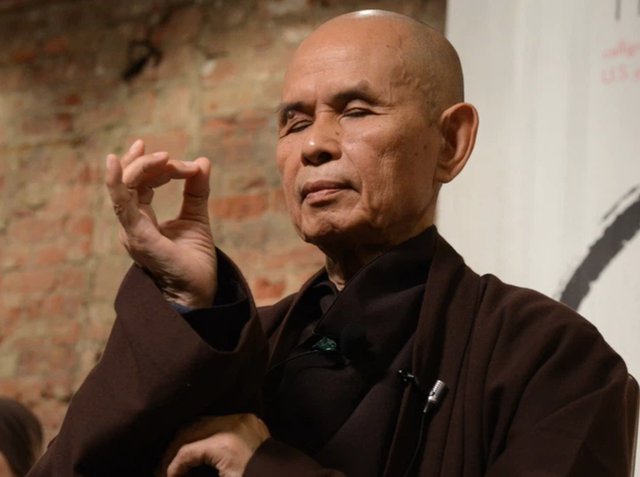

| Thich Nhat Hanh, October 11, 1926 - January 22, 2022 -- Creative Commons |

Thich Nhat Hahn’s spiritual focus however was not primarily on individual well-being. Rather, mindfulness emerged, for him, as a powerful force in his non-violent opposition to the war in Vietnam. Thich Nhat Hanh was an ally and an influence on the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.’s opposition to that war. In 1967, King nominated him for a Nobel Peace Prize, saying he was “an apostle of peace and non-violence, cruelly separated from his own people while they are oppressed by a vicious war which has grown to threaten the sanity and security of the entire world.” However, no prize would be awarded that year.

“Thich Nhat Hanh taught us that if we want a peaceful and just world, we have to learn how to be peaceful and just,” says longtime activist and mindfulness practitioner Lance Smith. “This takes learning to be present in a kind, clear, compassionate, and skillful way. A true Zen master, Thich Nhat Hanh practiced what he preached.”

His thoughts and words were featured in numerous articles in The Progressive, here are a few examples:

Labor and peace activist Sidney Lens, writing in the September 1967 issue, said: “In Paris I had a long talk with Thich Nhat Hanh, the impressive Buddhist monk who is associated with Thich Tri Quang and the Unified Buddhist Church. Nhat Hanh, a man of rare integrity and insight, has his own plan for ending the war. Much of it is contained in his sensitive book, Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire, which is now in its fourth edition in Saigon and has sold more than 100,000 copies even though its circulation there is illegal. For Nhat Hanh, the issue is no longer victory—for either side—but survival, and the only basis for survival is for the United States to permit the democratic voice of the South Vietnamese people to express itself. What the South Vietnamese want more than anything else, he told me, is peace—a view confirmed by a poll made in South Vietnam for the Columbia Broadcasting System.”

Laurence M. Stern, a former reporter and editor at The Washington Post, who wrote for The Progressive about Washington, D.C., from 1964 until 1979 under the pseudonym “Potomacus,” provided us this portrait in July 1971:

In his brown Buddhist robes the Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh is a slight figure who seems, but for the suffering in his eyes, to be barely out of his adolescence. In fact he is forty-four years old, a monk since he joined a Zen community at the age of sixteen, the author of ten books, including three acclaimed volumes of poetry. Since 1966 Thich Nhat Hanh has been in exile from his native South Vietnam, unable to return because of his outspoken opposition to the war and to the military rulers in Saigon. He is the observer of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam at the Paris negotiations. A few weeks ago he visited Washington—perhaps his last such visit, since Saigon has announced it is revoking his passport—and offered these three steps that the United States can take to end the war in Vietnam:

“One—to declare unilaterally an immediate cease-fire, stopping all aerial bombing and ground missions and the use of chemical defoliants, and withdrawing to positions of self-defense. This action will not only stop the destruction of human life but will also clearly prove the American intention to end the war. It will draw considerable sympathy and support within and without Vietnam. It will encourage Vietnamese on both sides to stop shooting at each other.

“Two—to pledge complete withdrawal of all U.S. military forces from Vietnam and to announce a timetable for such withdrawal. This action will assure Vietnamese who support the National Liberation Front that foreign soldiers are not going to be in the country any more, and there is no reason to support a war that kills only Vietnamese. It will also allow Vietnamese on both sides to come together to seek a political settlement.

“Three—to stop supporting the present Saigon government in its attempt to impose itself longer on the Vietnamese people. This action will lead to the end of corruption and dictatorship in Saigon, to the release of political prisoners, to the restoration of religious and civil liberties, and to the formation of a peace government that can get the overwhelming support of the Vietnamese people.”

The most urgent of these steps, the indispensable step, is a ceasefire, Thich Nhat Hanh insisted. In a voice barely audible, he said: “The Vietnamese people are so tired of war. Vietnamization is just an attempt to continue the war with fewer American troops but more American arms. What we need most, what we need now, is an ending of the killing.”

In a June 1977 article entitled “On Rage Remembered,” Ann Morrissett Davidon of the War Resisters League wrote: “But then sometimes there are dramatic images—even if conveyed by the television screen, as in the 1960s—which remind us of the human meaning and historical scope of the struggle. Adrenalin mounts, hearts beat faster, rage rises against those insidious systems which let some men rise on the backs and bodies of other people while so often claiming to help them. . . . The men who happen to be in control will not like it, may not even know quite what they’re doing, but they need to know that we struggle not against them personally, but against the systems of profit and power by which they exploit human beings and the earth’s resources. As the Vietnamese poet-priest Thich Nhat Hanh wrote in the midst of that cruelly protracted and embittering war:

Men cannot be our enemies.

Not even men called “Viet Cong.”

If we kill men,

What brothers have we left,

With whom shall we live then?

And most recently, in September 2009, in a review of the book Fire and Ink: An Anthology of Social Action Writing. Then-editor Matthew Rothschild noted: “You’ll find a lot of inspiration and wisdom here. One essay by Thich Nhat Hanh cautions us that raising our voice is not enough: ‘To educate people for peace, we can use words or we can speak with our lives.’ ”

In a time when the drumbeat for war seems loud in the air, we remember the lessons of this engaged Buddhist monk.

-------------------

The Progressive was founded and co-edited as "Lafollete's Weekly,"by Senator Robert M. Lafollete, Sr. and his spouse, the feminist journalist, suffragist, and peace activist, Belle Case, in 1909. Leaders of the modern Progressive Movement, "Fighting Bob"was an important force for social and economic justice. A fierce advocate for an anti-interventionist American foreign policy, he held public office for decades. Belle Case LaFollette, who provided "much of the intellectual sophistication behind the Progressive Movement,"was the first woman to graduate from the University of Wisconsin law school. She founded the Women's Peace Party (later the Women's International League Peace and Freedom), and was the magazine's editor when it became The Progressive in 1929.

As a third party candidate for President in 1924, "Fighting Bob" LaFollette had the endorsement of Eugene Debs, W.E.B Dubois, Margaret Sanger and other prominent progressive leaders. In that election, he won nearly one of five votes cast, mostly in rural and working class districts. He died at age 70 a year later.

Today, The Progressive endures as an important source of in-depth analysis and commentary in support of the continuing movement for human liberation. Continuing to call out all forms of systemic oppression, it now also maintains an on-line presence. Challenging the narrative furthered by the corporate media, The Progressive perseveres a clear "voice for peace, social justice, and the common good," relying on subscriptions and donations for their continued existence.

I found the brief video "pitch" below compelling. Besides my pitch here, I just pitched in again. How about you?

Yours in One Love,

Lance

No comments:

Post a Comment